Sake(酒), the beloved Japanese rice wine, has been a cherished part of Japanese lifestyle and culture for centuries. Its rich history and cultural significance have captivated people worldwide, particularly with the growing popularity of Japanese cuisine. In this blog, we will explore the fascinating history of sake, delve into the intricate sake-making process, and learn how to appreciate the distinct flavors and aromas of this traditional beverage.

The History of Sake Production

Although the exact origins of sake are unclear, evidence suggests that it has been produced in Japan since the Yayoi period (300 B.C – 250 A.D), when rice cultivation was introduced from China. During the Heian period (794 – 1185), sake was primarily made in temples and shrines until breweries started making it during the Muromachi period (1333 – 1573). The Muromachi Shogunate even imposed taxes on sake production as a source of government revenue.

In the late 16th century, sake began undergoing a heat sterilization process called hiire (火入れ) and large wooden vats were developed for storing large volumes of sake at one time. But it was during the Edo period (1603 – 1868) that sake production became a thriving industry. The process was further refined with the introduction of distilled alcohol for adjusting the flavor and preserving it longer.

In 1904, the National Research Institute of Brewing was established to conduct scientific research into sake making and discover new ways and technologies to improve its production. Today, sake has become a cultural icon and is enjoyed by people all over the world.

The Sake Making Process

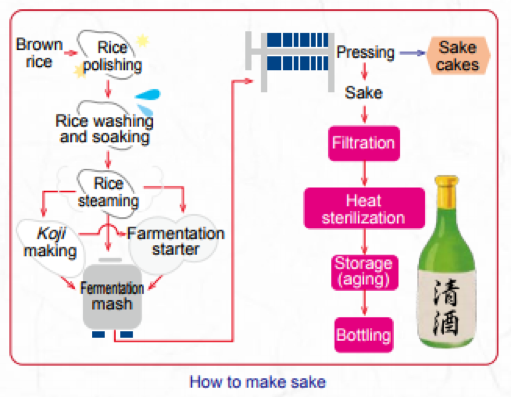

Sake is made from rice, koji, and water, which are put through the process of fermentation with yeast. The yeast produces alcohol and CO2 from the breakdown of the carbohydrates in rice. The resulting product is a fermentation mash, and the alcohol is separated by pressing the mash and removing the solid sediments. The alcohol is then further filtered, sterilized, and aged before it is eventually bottled and sold for consumption.

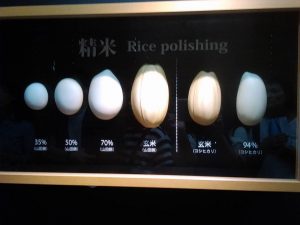

Special varieties of rice called shuzo-kotekimai are grown specifically for sake making, and the rice used for sake making is white, polished rice. Polishing the rice is important because it removes the outer layer of the rice (bran) to remove any excess proteins and oils and develop its own special aroma. Since the rice contains protein, koji is used to break down that protein into amino acids and peptides, which provide umami(旨味), taste. The degree of polish also determines the quality of the sake, and the highest quality sake is made with rice polished to 50% or more. Normal table rice is 10% polished, but sake rice is usually 30% polished. Special refined rice wines (daiginjo-shu) are polished 50% or more before being fermented. Some of the finest daiginjo-shu is made with 70% polished rice.

After the bran has been polished from the rice, it is soaked in water to absorb adequate moisture. Sake is made during the winter season, and cold water is used, making washing the rice a very arduous job. The rice is then drained and covered with cloth overnight before being steamed. Steaming the rice makes it easier for the koji enzymes to break it down. Steamed sake rice is still firm, unlike table rice, which can get sticky, and that distinction is important because koji works best when the rice grains are separated from each other.

Koji is made by cooling down the steamed rice and bringing it to a koji room where the rice is spread out on a long table called the toko. The spores of the koji (Aspergillus oryzae) fungus are then spread over the rice, mixed together, and covered in a cloth to keep the temperature and humidity constant. The koji will produce heat from its metabolism so the mass is spread out again to regulate the temperature. White areas then form over the rice grains called haze, which are areas of koji growth, and it completely covers the grains after two days. The koji mold produces enzymes, which are a key component in the fermentation process to produce starch from the rice into sugar. The addition of yeast then makes it possible to convert the sugar into alcohol.

Water is also a crucial component in sake production since 80% of sake is composed of water. The ideal water constituent for sake making is higher in hardness, higher in phosphorus, and lower in iron. Iron content in the water used for sake production needs to be kept as low as possible to prevent discoloration and an unpleasant aroma. An iron content of 0.02 ppm or lower is ideal, so regions with very low iron content water are usually where sake breweries are put up, like at Nada in Kobe and Fushimi in Kyoto.

How to Evaluate Sake Quality

Evaluating sake quality involves assessing its color, aroma, and taste.

Color:

The color of sake can indicate its age. Dark yellow or brown sake has been stored for a long time. The kikichoko, a special ceramic cup, has blue circles at the bottom to help identify the color and transparency.

Aroma:

The strength and balance of the aroma are evaluated. Aged sake tends to have a rich, fruity aroma called ginjo.

Taste:

Sake is classified based on its sweetness/dryness, richness/lightness, and presence/absence of umami. Sake with lots of sugar tends to be sweet, while less sugar content makes it taste dry. Acidity also plays a role, so even if the sugar level is the same, acidic sake will taste drier, while less acidic sake will be sweeter. Rich sake results from a high content of alcohol, sugar, acid, or amino acids, while light sake results from reduced content of these ingredients. Sake with high levels of amino acids will become unpleasant if aged too long.

Sake can be consumed at various temperatures and paired with different dishes. Ginjo-shu has the aroma of apples or bananas and is best served cool, and it is best consumed during the first half of dinner. Junmai-shu usually has a rich taste and is best paired with rich-tasting food cooked with soy sauce, sugar, and oils. Honjozo-shu can be consumed at any temperature and generally pairs well with any dish.

Different varieties of sake are available, and it is up to your individual tastes to find the right one for you. Sake is evaluated based on its color, taste, and aroma, and professionals use a special ceramic cup called a kikichoko to evaluate sake. If you’re looking to explore the variety of sake available, try different types and find the right one that suits your individual taste.

Plan on Visiting Japan in the future?

If you’re visiting Japan for sight-seeing and want to get the most out of your experience, then purchasing the JR Pass is a great option to consider!